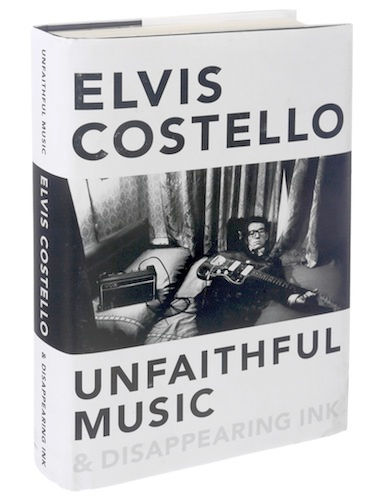

Elvis Costello: Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink

- Neil Morton

- Jan 21, 2017

- 3 min read

Updated: May 7, 2020

Neil Morton

Has there ever been a musical autobiography so riven with guilt and self-reproach as this? Despite examples of evasion about certain episodes of his life, the former Declan Patrick MacManus, now 62, is disarmingly honest and courageous in confronting his weaknesses, from the Attractions to the distractions, from angry young man to elder statesman.

The celebrated wordsmith can be as cryptic as his lyrics and there is a certain forgivable self-regard amid the hero worship through all the collaborations with icons such as Paul McCartney, George Jones, Burt Bacharach, Allen Toussaint, T Bone Burnett, the Brodsky Quartet and Bob Dylan.

The most fascinating moments in a remarkably articulate if overlong tome – as one would expect from a writer skilled in verbal gymnastics – involve time spent with his beloved father Ross, a gifted singer, musical mimic and entertainer with the Joe Loss Orchestra, who would himself be worthy of a biography. The description of his dad’s slow decline is particularly poignant.

Costello’s take on the power of a song is memorable. Discussing his approach to the lyrics for the sublime Shipbuilding, written with Clive Langer in the wake of the Falklands War and covered beautifully by Robert Wyatt, he asks: ‘Can a mere song change people’s minds? I doubt that it is so but a song can infiltrate your heart and the heart may change your mind. The extent of my ambition for Shipbuilding was to make the listener less lonely. Every shipyard in those towns and cities that built the great warships, merchantmen and liners had diminishing prospects, if not shuttered gates. That’s been reason enough to sing this song ever since, and it gets sadder by the year.’

Our paths actually crossed in the early 70s though Costello would struggle to recall. I was helping to run a folk and blues club at the Mitre pub in Liverpool called the Garrett. Declan had joined Allan Mayes’ band Rusty who took on a residency at a similar club in Dale Street called the Temple Bar. I later played in a folk-blues trio, Breakdown, with John Pearson and Raphael Callaghan, and wrote a song recorded by About Time called Burning Out Of The Blues which talked about those clubs and those times.

Declan was obviously bound for higher deeds. We saw Rusty, reduced to a duo, at the Temple Bar and again when they stole the show at the Mitre on one of our open-mic nights (simply called singers’ nights then). Certain thoughts struck us whenever we heard them play: vocal power, impact, self-confidence, bravado, daring, talent, stridence, ambition. Rusty did not last long; Declan headed back to London for a new chapter and a new name leaving Allan behind to his day job and his regular club gigs. At least he managed to secure a paid guest spot at the Garrett. Mayes, in fact, did very well for himself, making a living and seeing the world playing on cruise ships, and now has a residency with a lady called LaDonna at a club in Austin, Texas.

Elvis, as he soon became, enjoyed a reunion with his old partner while promoting his Unfaithful Music book in Austin in 2015. They were obviously still great mates, but naturally a bit Rusty. Mayes had kept meticulous records of all their 70s gigs, their playlists complete with lyrics (including those for Maureen and Dan, a song about ‘the beauty contest of fame’, which morphed into Costello’s 1980 song Ghost Train) and the paltry fees they were paid. I cannot remember how much the Garrett put in Allan Mayes’ hand that memorable night, but it would not have done him justice.

The last word on Rusty and those early playing days goes to Costello in Unfaithful Music: ‘If there had been a moment after the Beatles hit when it seemed any Liverpool scruff with a guitar could get signed, that moment had definitely passed.’ He pays tribute to his friend’s ‘superior musicianship and more melodious voice’ as Rusty struggled to make an impact at traditional folk clubs, poetry evenings and pubs whose clientele demanded the hits of the day not esoteric, self-penned songs they had never heard of. Breakdown and About Time knew the feeling.

Costello’s parents had split up; he was living with his mum on Merseyside while dad was at the old house near Twickenham. ‘I knew that I’d eventually have to go back to London. I realised after a couple of years that if I stayed in Liverpool, I’d paddle around and around the same shallow pool of possibilities and wake up one day at 30, embittered and disillusioned with music.’ As we know, he never looked back.

Robert Wyatt’s version of Shipbuilding accompanied by Costello...